Late last week, Google announced something called the Privacy Sandbox has been rolled out to a “majority” of Chrome users, and will reach 100% of users in the coming months. But what is it, exactly?

The new suite of features represents a fundamental shift in how Chrome will track user data for the benefit of advertisers. Instead of third-party cookies, Chrome can now tap directly into your browsing history to gather information on advertising “topics” (more on that later).

In development since 2019, this change has attracted a great deal of controversy, as some commentators have deemed it invasive in terms of privacy.

Understanding how it works – and whether you want to opt in or out – is important, since Chrome remains the most widely used browser in the world, with a 63% market share as of May 2023 (Safari is in second place with 13%).

Wait, what is a cookie?

In 1994, computer engineer Lou Montulli at Netscape revolutionised the way we browsed the internet with his invention of the “cookie”. For the first time, web pages could remember our passwords, preferences, language settings and even shopping carts.

This method was supposed to be a private exchange of information just between a user and a website – what’s known as a first-party cookie. But within two years, advertisers worked out how to “hack” cookies to track users. These are third-party cookies.

You can think of a first-party cookie like a shop assistant who listens to your preferences and is happy to hold your bags or clothes while you make your selection – but only while you are inside their store.

A third-party cookie is like a bug from an old spy movie. It listens to everything in your room, but only shares the info with its allies. The “spy” can place this cookie on other people’s sites, to record what you visit and what data you enter. If you’ve ever wondered how Facebook has served you an ad about something related to a news story you just read, chances are it’s because you have third-party cookies enabled.

Unregulated online tracking and surveillance via cookies were the default until 2018, when the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) were introduced. If you have noticed more pop-ups notifying you of cookies and asking for your informed consent, you have the GDPR and CCPA to thank.

The first browsers to turn off support for third-party cookies were Apple’s Safari in 2017 and Mozilla’s Firefox in 2019.

But Google is also a major online advertising company, with ads making up 57.8% of Google’s revenue as of 2023. They have been slowest off the mark in turning off third-party cookies in Chrome. With the introduction of the Privacy Sandbox, they now hope to start turning cookies off sometime in 2024.

How is the Privacy Sandbox different from cookies?

The details on how the Privacy Sandbox collection of features works are rather technical. But here are a few of the most important aspects.

Instead of using third-party cookies to serve you ads across the internet, Chrome will provide something called advertising Topics. These are high-level summaries of your browsing behaviour, tracked locally (such as in your browsing history), that companies can access on request to serve you ads on particular subjects.

Additionally, there are features such as Protected Audience that can serve you ads for “remarketing” (for example, Chrome tracked you visiting a listing for a toaster, so now you will get ads for toasters elsewhere), and Attribution Reporting, that gathers data on ad clicks.

In short, instead of third-party cookies doing the spying, the features these cookies enable will be available directly within Chrome.

Is user tracking necessarily bad?

While Google pitches the Privacy Sandbox as something that will improve user privacy, not everyone agrees.

If these features are switched on, Google – one of the world’s biggest advertising companies – is essentially able to listen to you everywhere on the web.

Tracking technology can arguably benefit us as well. For example, it could be helpful if an online store reminds you every three months you need a new toothbrush, or that this time last year you bought a birthday card for your mum.

Offloading cognitive effort, such as reminders like these, is a great way automation can assist humanity. When used in situations where pinpoint accuracy is required, it can make our lives easier and more pleasant.

However, if you are not comfortable with surveillance, the alternative to third-party cookies may not necessarily be the new Privacy Sandbox in Chrome.

The alternative is to completely disable tracking altogether.

What can you do?

If you don’t want your online activities to be tracked for advertising purposes, there are a few straightforward choices.

By far the most private browsers are specialist non-tracking browsers that prioritise no tracking, such as DuckDuckGo and Brave. But if you don’t want to get that nerdy, Safari and Firefox already have third-party cookies blocked by default.

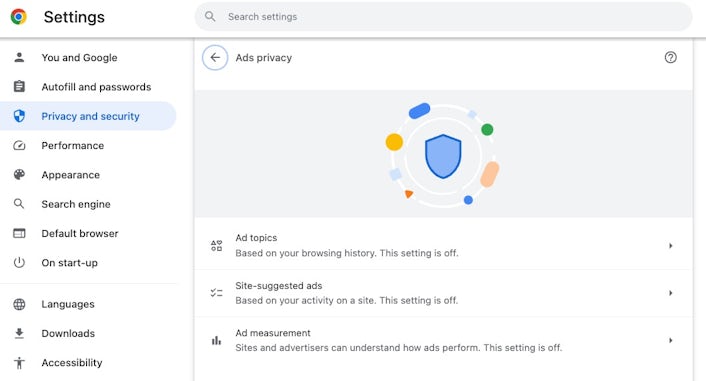

The tools found in Google Chrome are nestled under Settings - Ads privacy. You can toggle each section on or off individually, and click on them to look at more details. Screenshot via The Conversation

If you don’t mind some useful targeted advertising, you can leave the Chrome Privacy Sandbox settings on.

If you want to adjust these settings or switch them off, click the three dots in the upper-right corner and go to Settings > Privacy and Security > Ad privacy. It’s unclear if toggling these features off will stop Chrome from collecting these data altogether, or if it just won’t share the data with advertisers. You can find out more details about each feature on the Google Chrome Help page.

Lastly, it’s good to remember nothing truly comes for free. Software costs money to develop. If you’re not paying towards that, then it’s likely you – or your data – are the product. We need to revolutionise how we think about our own data and what value it truly holds.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media enquiries: Please contact the Media Team media@usc.edu.au